Em uma empresa, o diretor de um departamento percebeu que

Pedro, um dos funcionários, tinha cometido alguns erros em seu

trabalho e comentou:

“Pedro está cansado ou desatento.”

A negação lógica dessa afirmação é:

Mining tourism in Ouro Preto

Ouro Preto is surrounded by a rich and varied natural

environment with waterfalls, hiking trails and native vegetation

partially protected as state parks. Parts of these resources are

used for tourism. Paradoxically, this ecosystem contrasts with the

human occupation of the region that produced, after centuries, a

rich history and a cultural connection to mining, its oldest

economic activity which triggered occupation. The region has an

unlimited potential for tourism, especially in specific segments

such as mining heritage tourism, in association or not with the

existing ecotourism market. In fact, in Ouro Preto, tourism,

history, geology and mining are often hard to distinguish; such is

the inter-relationship between these segments.

For centuries, a major problem of mining has been the reuse of

the affected areas. Modern mining projects proposed solutions to

this problem right from the initial stages of operation, which did

not happen until recently. As a result, most quarries and other

old mining areas that do not have an appropriate destination

represent serious environmental problems. Mining tourism

utilizing exhausted mines is a source of employment and income.

Tourism activities may even contribute to the recovery of

degraded areas in various ways, such as reforestation for leisure

purposes, or their transformation into history museums where

aspects of local mining are interpreted.

Minas Gerais, and particularly Ouro Preto, provides the strong

and rich cultural and historical content needed for the

transformation of mining remnants into attractive tourism

products, especially when combined with the existing cultural

tourism of the region. Although mining tourism is explored in

various parts of the world in extremely different social, economic,

cultural and natural contexts, in Brazil it is still not a strategy

readily adopted as an alternative for areas affected by mining

activities.

(Lohmann, G. M.; Flecha, A. C.; Knupp, M. E. C. G.; Liccardo, A.

(2011). Mining tourism in Ouro Preto, Brazil: opportunities and

challenges. In: M. V. Conlin; L. Jolliffe (eds). Mining heritage and

tourism: a global synthesis. New York: Routledge, pp. 194-202.)

The sentence that best explains “Mining tourism utilizing exhausted mines is a source of employment and income.” (l. 18-19) is:

TEXT 3

Sustainable mining – oxymoron or a way of the future?

Mining is an activity that has persisted since the start of humans

using tools. However, one might argue that digging a big hole in

the ground and selling the finite resources that come out of that

hole is not sustainable, especially when the digging involves the

use of other finite resources (i.e. fuels) and produces a lot of

greenhouse gases.

The counter argument could go along the lines that minerals are

not being lost or destroyed through mining and mineral

processing – the elements are being shifted around, and

converted into new forms. Metals can even be extracted from

waste, seawater or even sewage, and recycled. But a more simple

argument is possible: a mine can be sustainable if it is

economically, socially and environmentally beneficial in the short

and long term. To be sustainable, the positive benefits of mining

should outweigh any negative impacts. […]

Social positives are often associated with mines in regional areas,

such as providing better amenities in a nearby town, or providing

employment (an economic and social positive). Social negatives

can also occur, such as dust, noise, traffic and visual amenity.

These are commonly debated and, whilst sometimes

controversial, can be managed with sufficient corporate

commitment, stakeholder engagement, and enough time to work

through the issues. Time is the key parameter - it may take

several years for a respectful process of community input, but as

long as it is possible for social negatives to be outweighed by

social positives, then the project will be socially sustainable.

It is most likely that a mine development will have some

environmental negatives, such as direct impacts on flora and

fauna through clearing of vegetation and habitat within the mine

footprint. Some mines will have impacts which extend beyond

the mine site, such as disruption to groundwater, production of

silt and disposal of waste. Certainly these impacts will need to be

managed throughout the mine life, along with robust

rehabilitation and closure planning. […]

The real turning point will come when mining companies go

beyond environmental compliance to create 'heritage projects'

that can enhance the environmental or social benefits in a

substantial way – by more than the environmental offsets

needed just to make up for the negatives created by the mine. In

order to foster these innovative mining heritage projects we need

to promote 'sustainability assessments' - not just 'environmental

assessments'. This will lead to a more mature appreciation of the

whole system whereby the economic and social factors, as well as

environmental factors, are considered in a holistic manner.

(adapted from https://www.engineersaustralia.org.au/westernaustralia-division/sustainable-mining-oxymoron-or-way-future.

Retrieved on August 10, 2015)

As regards the content of Text 3, analyse the assertions below: I - It is well-known that the resources extracted from mines are endless. II - The social negative impacts of mining may be minimized as time goes by. III - Sustainable assessment has a wider field of action than environmental assessment. IV - There is agreement that negative impacts of mining are restricted to the site. The correct sentences are only:

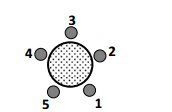

Abel, Bruno, Caio, Diogo e Elias ocupam, respectivamente, os

bancos 1, 2, 3, 4 e 5, em volta da mesa redonda representada

abaixo.

São feitas então três trocas de lugares: Abel e Bruno trocam de

lugar entre si, em seguida Caio e Elias trocam de lugar entre si e,

finalmente, Diogo e Abel trocam de lugar entre si.

Considere as afirmativas ao final dessas trocas:

• Diogo é o vizinho à direita de Bruno.

• Abel e Bruno permaneceram vizinhos.

• Caio é o vizinho à esquerda de Abel.

• Elias e Abel não são vizinhos.

É/são verdadeira(s ):

Indique, dentre os documentos listados abaixo, o que representa uma espécie documental:

A história dos arquivos está intimamente ligada à história do suporte da informação administrativa. Relacione os principais suportes utilizados com o material do qual ele é feito: I – placas ( ) folhas (vegetal) II – papiro ( ) couro III – pergaminho ( ) argila IV – códices A sequência correta é:

Considere os itens a seguir: I – Jéssica de Andrade Ramos II – Janaína Aguiar Rangel III – Jonas Alencar Rabello IV – Julio de Almeida Reis Junior V – Joel de Alcântara Reis Neto Utilizando-se as regras de alfabetação segundo o método de classificação alfabético, a sequência correta é:

Em um arquivo permanente, o instrumento de pesquisa que proporciona uma visão geral do acervo é:

Os documentos digitais podem ser classificados em estáticos e interativos, e esses últimos em dinâmicos e não dinâmicos. Um exemplo de documento digital interativo não dinâmico seria:

O arquivista, para planejar que tipo de mobiliário deve obter para dispor um acervo de documentos textuais, deve levar em consideração:

Mining tourism in Ouro Preto

Ouro Preto is surrounded by a rich and varied natural

environment with waterfalls, hiking trails and native vegetation

partially protected as state parks. Parts of these resources are

used for tourism. Paradoxically, this ecosystem contrasts with the

human occupation of the region that produced, after centuries, a

rich history and a cultural connection to mining, its oldest

economic activity which triggered occupation. The region has an

unlimited potential for tourism, especially in specific segments

such as mining heritage tourism, in association or not with the

existing ecotourism market. In fact, in Ouro Preto, tourism,

history, geology and mining are often hard to distinguish; such is

the inter-relationship between these segments.

For centuries, a major problem of mining has been the reuse of

the affected areas. Modern mining projects proposed solutions to

this problem right from the initial stages of operation, which did

not happen until recently. As a result, most quarries and other

old mining areas that do not have an appropriate destination

represent serious environmental problems. Mining tourism

utilizing exhausted mines is a source of employment and income.

Tourism activities may even contribute to the recovery of

degraded areas in various ways, such as reforestation for leisure

purposes, or their transformation into history museums where

aspects of local mining are interpreted.

Minas Gerais, and particularly Ouro Preto, provides the strong

and rich cultural and historical content needed for the

transformation of mining remnants into attractive tourism

products, especially when combined with the existing cultural

tourism of the region. Although mining tourism is explored in

various parts of the world in extremely different social, economic,

cultural and natural contexts, in Brazil it is still not a strategy

readily adopted as an alternative for areas affected by mining

activities.

(Lohmann, G. M.; Flecha, A. C.; Knupp, M. E. C. G.; Liccardo, A.

(2011). Mining tourism in Ouro Preto, Brazil: opportunities and

challenges. In: M. V. Conlin; L. Jolliffe (eds). Mining heritage and

tourism: a global synthesis. New York: Routledge, pp. 194-202.)

The opposite of the underlined word in “are often hard to distinguish” (l. 11) is:

TEXT 2

Innovation is the new key to survival

[…]

At its most basic, innovation presents an optimal strategy for

controlling costs. Companies that have invested in such technologies

as remote mining, autonomous equipment and driverless trucks and

trains have reduced expenses by orders of magnitude, while

simultaneously driving up productivity.

Yet, gazing towards the horizon, it is rapidly becoming clear that

innovation can do much more than reduce capital intensity.

Approached strategically, it also has the power to reduce people and

energy intensity, while increasing mining intensity.

Capturing the learnings

The key is to think of innovation as much more than research and

development (R&D) around particular processes or technologies.

Companies can, in fact, innovate in multiple ways, such as leveraging

supplier knowledge around specific operational challenges,

redefining their participation in the energy value chain or finding new

ways to engage and partner with major stakeholders and

constituencies.

To reap these rewards, however, mining companies must overcome

their traditionally conservative tendencies. In many cases, miners

struggle to adopt technologies proven to work at other mining

companies, let alone those from other industries. As a result,

innovation becomes less of a technology problem and more of an

adoption problem.

By breaking this mindset, mining companies can free themselves to

adapt practical applications that already exist in other industries and

apply them to fit their current needs. For instance, the tunnel boring

machines used by civil engineers to excavate the Chunnel can vastly

reduce miners' reliance on explosives. Until recently, those machines

were too large to apply in a mining setting. Some innovators,

however, are now incorporating the underlying technology to build

smaller machines—effectively adapting mature solutions from other

industries to realize more rapid results.

Re-imagining the future

At the same time, innovation mandates companies to think in

entirely new ways. Traditionally, for instance, miners have focused on

extracting higher grades and achieving faster throughput by

optimizing the pit, schedule, product mix and logistics. A truly

innovative mindset, however, will see them adopt an entirely new

design paradigm that leverages new information, mining and energy

technologies to maximize value. […]

Approached in this way, innovation can drive more than cost

reduction. It can help mining companies mitigate and manage risks,

strengthen business models and foster more effective community

and government relations. It can help mining services companies

enhance their value to the industry by developing new products and

services. Longer-term, it can even position organizations to move the

needle on such endemic issues as corporate social responsibility,

environmental performance and sustainability.

(http://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/ru/Document

s/energy-resources/ru_er_tracking_the_trends_2015_eng.pdf)

The excerpt “one might argue” (l.2) expresses:

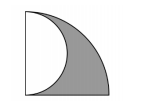

A região sombreada na figura é conhecida como “barbatana de

tubarão" e foi construída a partir de um quadrante de círculo de

raio 4 e de um semicírculo.

A área dessa “barbatana de tubarão" é:

Turistas são indivíduos em viagem para locais fora de sua região de residência, por período mínimo de uma noite, com motivação de negócios ou lazer. De acordo com a Organização Mundial do Turismo, para fins de planejamento estatístico, o período máximo de permanência para ser contabilizado como turista é de:

O turismo é um setor gerador de receitas, podendo ser até a principal fonte de recursos de uma determinada região. O cálculo do impacto econômico em turismo pode ser uma atividade complexa, por requerer exame de diferentes aspectos da economia que são afetados pelas despesas turísticas. Os efeitos econômicos associados às despesas turísticas podem ser: