In the 1980s, plant genetic resources were considered under international law to be a common heritage of mankind, and were therefore classified as goods that cannot be owned. However, this status was strongly rejected by many emerging countries because it gave pharmaceutical and seed companies (mostly from rich countries) free access to their genetic resources without being required in any way to redistribute a share of their profits.

These countries scored a victory with the signing of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992 and the TRIPS agreement in 1995. Genetic resources now come under the control of sovereign countries, and some property rights can be recognized to the indigenous communities on the resources that they have been conserving from generation to generation. States are now required to organize these “collective intellectual property rights” in such a way that any local resource conserved in this manner will generate dividends for these populations when used by multinational firms.

The now well-known concept of Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit-Sharing (ABS) emerged in the second half of the 1990s. Their aim was to organize a biological diversity marketplace capable of enhancing the value of the genetic resources of countries of the South, which cannot refuse access to these resources. In addition, these countries can now claim a share of the profits that may result from their use.

In short, the change in the status of genetic resources from common heritage of mankind to a good that can be owned under national sovereignty took place in the early 1990s at the request of countries of the South and to their benefit, and the ABS mechanism is a fine example of intellectual property rights set up in the interest of the people of these countries.

In a general sense, this analysis is fairly accurate and could constitute an argument to be used against those who are of the opinion that the spread of intellectual property rights is an obstacle to the development of the South. However, the issue today is whether the South gained anything by playing this card. In answering this question, it is important to more clearly emphasize the deep connection—often overlooked—between the conservation of genetic resources and their practical use.

Internet: <https://shs.cairn.info/journal> (adapted).

Based on the preceding text, judge the following items.

In the 1980s, genetic resources were regarded as private property under international law, allowing multinational corporations to control them freely.

Art and Banking: from the House of Medici to Deutsche Bank

An example in coexistence – that is how we might define the intersection between the banking sector and the art world since the Middle Ages. Esses dois campos distintos gradualmente desenvolveram diversos pontos de contato, muitos dos quais persistem há séculos.In 2020, faced with the spread of Covid-19, people’s interest in illiquid art investments has diminished, but, given the long history of interactions between bankers and people of art, we may conclude that the historical trend is bound to spring back.

The first examples of cross-pollination between banking and art can be traced back to the 13th century, when wealthy financiers would acquire or commission masterpieces as a means of penitence for their sins and as a marker of social status.By the 16th century, as religious influences receded, bankers were motivated by the luxury of becoming patrons of the arts, mythologizing their individual power through art and architecture. The most well-known example of this trend was the Medici family, which sponsored the artistic development and posterity of Renaissance virtuosos such as Donatello, Michelangelo, Sandro Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci.In the 17th century, art became a consumer commodity, and would often be used as currency; artists were also known to use their work as collateral for loans. In the 18th and 19th centuries, banks would provide immeasurable support to the founders of the earliest art academies and national museums.

The turning point in this journey for art and banking came in the 1940s, when the art world’s centre of gravity suddenly shifted straight across the Atlantic, from Paris to Manhattan.In light of this tectonic shift, Chase Manhattan Bank president David Rockefeller launched the bank’s art collection programme, which would define the future vision of nearly every finance institution globally. It became one of the first few commercial art collections, as we know them today.

Currently, one of the largest commercial collections of artworks is owned by Deutsche Bank. From humble beginnings with the acquisition of the first few paintings, sculptures, photographs and graphics in 1979, it now reaches an estimated value of 500 million U.S. dollars – perhaps a diminutive figure in the grand scheme of things, but Deutsche Bank prefers to feature young, promising artists.The most valuable pieces in the Deutsche Bank collection had been acquired well before their respective authors became household names. Thus, the bank purchased Abstraktes Bild (Faust), Gerhard Richter’s 1981 triptych, for 12 million dollars; in February 2020, it was sold for triple the amount to an anonymous buyer.

Over time, we may observe how the relationship between artists and bankers has grown increasingly transactional since the Medici era. Today, art is still a hallmark of socioeconomic status, even though most bankers also treat art both as a financial investment and interior decoration that shapes the organisational climate and inspires personnel.Art collecting is often included under the umbrella of a marketing strategy, as a peculiar language of broadcasting organisational values. Where the common journey of banking and art may lead in later decades or centuries is difficult to predict, but one thing remains clear: art will remain a point of interest for bankers.

Available at: https://signetbank.com/en/news/art-and-banking--from-the-house-of-medici-to-deutsche-bank/. Retrieved on: March, 8th, 2025. Adapted.

In the fragment in the third paragraph of the text “David Rockefeller launched the bank’s art collection programme, which would define the future vision of nearly every finance institution globally”, the expression in bold refers to

Text I

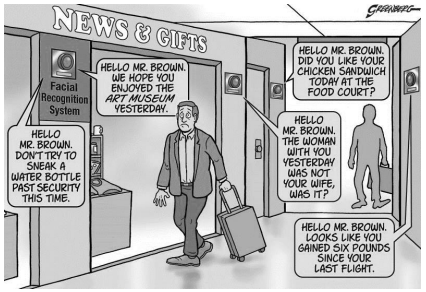

Understanding bias in facial recognition technologies

Over the past couple of years, the growing debate around automated facial recognition has reached a boiling point. As developers have continued to swiftly expand the scope of these kinds of technologies into an almost unbounded range of applications, an increasingly strident chorus of critical voices has sounded concerns about the injurious effects of the proliferation of such systems on impacted individuals and communities. Critics argue that the irresponsible design and use of facial detection and recognition technologies (FDRTs) threaten to violate civil liberties, infringe on basic human rights and further entrench structural racism and systemic marginalisation. In addition, they argue that the gradual creep of face surveillance infrastructures into every domain of lived experience may eventually eradicate the modern democratic forms of life that have long provided cherished means to individual flourishing, social solidarity and human self-creation.

Defenders, by contrast, emphasise the gains in public safety, security and efficiency that digitally streamlined capacities for facial identification, identity verification and trait characterisation may bring. These proponents point to potential real-world benefits like the added security of facial recognition enhanced border control, the increased efficacy of missing children or criminal suspect searches that are driven by the application of brute force facial analysis to largescale databases and the many added conveniences of facial verification in the business of everyday life.

Whatever side of the debate on which one lands, it would appear that FDRTs are here to stay.

Adapted from: understanding_bias_in_facial_recognition_technology.pdf

In the last sentence, the author states that facial detection and recognition technologies

Text II

From: https://www.cartoonmovement.com/cartoon/facial-recognition-0

The cartoon criticizes the fact that face recognition can be

In the early 2000s, when Amazon introduced its Kiva robots to automate warehouse operations, employees feared for their jobs as machines began taking over tasks previously performed by humans. Today, advances in gen AI and natural language processing, such as ChatGPT, are transforming many industries and raising similar concerns. However, unlike past automation technologies, gen AI has the unique potential to impact all job sectors, particularly given its fundamental ability to improve its capabilities over time – which promises to affect the workforce in ways that go beyond simple job replacement.

In new research, forthcoming in Management Science, we explore the impact gen AI has already had on the labor market by examining trends in demand for online freelancers. Our findings show significant short‑term job replacement after these tools were introduced, and that jobs prone to automation, like writing and coding, were the most affected by ChatGPT.Our research also examines how competition, job requirements, and employer willingness‑to‑pay have changed to better understand how the online job market is evolving with the rise of gen AI. Although still in its early stages, gen AI’s impact on online labor markets is already becoming discernible, suggesting potential shifts in long‑term labor market dynamics that could bring both challenges and opportunities.

To conduct our study, we analyzed 1.388.711 job posts from a leading global online freelancing platform from July 2021 to July 2023. Online freelancing platforms provide a good setting for examining emerging trends due to the digital, task‑oriented, and flexible nature of work on these platforms. We focus our analysis on the introduction of two types of gen AI tools: ChatGPT and image‑generating AI. Specifically, we wanted to understand whether the introduction and diffusion of these tools decreased demand for jobs on this platform and, if so, which types of jobs and skills are affected most and by how much.

Using a machine learning algorithm, we first grouped job posts into different categories based on their detailed job descriptions. These categories were then classified into three types: manual‑intensive jobs (e.g., data and office management, video services, and audio services), automation‑prone jobs (e.g., writing; software, app, and web development; engineering), and image‑generating jobs (e.g., graphic design and 3D modeling). We then examined the impact that the introduction of Gen AI tools had on demand across these different types of jobs.

We find that the introduction of ChatGPT and image‑generating tools led to nearly immediate decreases in posts for online gig workers across job types, but particularly for automation‑prone jobs. After the introduction of ChatGPT, there was a 21% decrease in the weekly number of posts in automation‑prone jobs compared to manual‑intensive jobs. Writing jobs were affected the most (30.37% decrease), followed by software, app, and web development (20.62%) and engineering (10.42%).

Internet: www.hbr.org (adapted).

According to the text, Artificial Intelligence is capable of huge impacts in the labor market, due to its ability of improvement.

In the early 2000s, when Amazon introduced its Kiva robots to automate warehouse operations, employees feared for their jobs as machines began taking over tasks previously performed by humans. Today, advances in gen AI and natural language processing, such as ChatGPT, are transforming many industries and raising similar concerns. However, unlike past automation technologies, gen AI has the unique potential to impact all job sectors, particularly given its fundamental ability to improve its capabilities over time – which promises to affect the workforce in ways that go beyond simple job replacement.

In new research, forthcoming in Management Science, we explore the impact gen AI has already had on the labor market by examining trends in demand for online freelancers. Our findings show significant short‑term job replacement after these tools were introduced, and that jobs prone to automation, like writing and coding, were the most affected by ChatGPT.Our research also examines how competition, job requirements, and employer willingness‑to‑pay have changed to better understand how the online job market is evolving with the rise of gen AI. Although still in its early stages, gen AI’s impact on online labor markets is already becoming discernible, suggesting potential shifts in long‑term labor market dynamics that could bring both challenges and opportunities.

To conduct our study, we analyzed 1.388.711 job posts from a leading global online freelancing platform from July 2021 to July 2023. Online freelancing platforms provide a good setting for examining emerging trends due to the digital, task‑oriented, and flexible nature of work on these platforms. We focus our analysis on the introduction of two types of gen AI tools: ChatGPT and image‑generating AI. Specifically, we wanted to understand whether the introduction and diffusion of these tools decreased demand for jobs on this platform and, if so, which types of jobs and skills are affected most and by how much.

Using a machine learning algorithm, we first grouped job posts into different categories based on their detailed job descriptions. These categories were then classified into three types: manual‑intensive jobs (e.g., data and office management, video services, and audio services), automation‑prone jobs (e.g., writing; software, app, and web development; engineering), and image‑generating jobs (e.g., graphic design and 3D modeling). We then examined the impact that the introduction of Gen AI tools had on demand across these different types of jobs.

We find that the introduction of ChatGPT and image‑generating tools led to nearly immediate decreases in posts for online gig workers across job types, but particularly for automation‑prone jobs. After the introduction of ChatGPT, there was a 21% decrease in the weekly number of posts in automation‑prone jobs compared to manual‑intensive jobs. Writing jobs were affected the most (30.37% decrease), followed by software, app, and web development (20.62%) and engineering (10.42%).

Internet: www.hbr.org (adapted).

The conjunction “whether” (third paragraph) in the extract “Specifically, we wanted to understand whether the introduction” can be correctly replaced by although.

In the early 2000s, when Amazon introduced its Kiva robots to automate warehouse operations, employees feared for their jobs as machines began taking over tasks previously performed by humans. Today, advances in gen AI and natural language processing, such as ChatGPT, are transforming many industries and raising similar concerns. However, unlike past automation technologies, gen AI has the unique potential to impact all job sectors, particularly given its fundamental ability to improve its capabilities over time – which promises to affect the workforce in ways that go beyond simple job replacement.

In new research, forthcoming in Management Science, we explore the impact gen AI has already had on the labor market by examining trends in demand for online freelancers. Our findings show significant short‑term job replacement after these tools were introduced, and that jobs prone to automation, like writing and coding, were the most affected by ChatGPT.Our research also examines how competition, job requirements, and employer willingness‑to‑pay have changed to better understand how the online job market is evolving with the rise of gen AI. Although still in its early stages, gen AI’s impact on online labor markets is already becoming discernible, suggesting potential shifts in long‑term labor market dynamics that could bring both challenges and opportunities.

To conduct our study, we analyzed 1.388.711 job posts from a leading global online freelancing platform from July 2021 to July 2023. Online freelancing platforms provide a good setting for examining emerging trends due to the digital, task‑oriented, and flexible nature of work on these platforms. We focus our analysis on the introduction of two types of gen AI tools: ChatGPT and image‑generating AI. Specifically, we wanted to understand whether the introduction and diffusion of these tools decreased demand for jobs on this platform and, if so, which types of jobs and skills are affected most and by how much.

Using a machine learning algorithm, we first grouped job posts into different categories based on their detailed job descriptions. These categories were then classified into three types: manual‑intensive jobs (e.g., data and office management, video services, and audio services), automation‑prone jobs (e.g., writing; software, app, and web development; engineering), and image‑generating jobs (e.g., graphic design and 3D modeling). We then examined the impact that the introduction of Gen AI tools had on demand across these different types of jobs.

We find that the introduction of ChatGPT and image‑generating tools led to nearly immediate decreases in posts for online gig workers across job types, but particularly for automation‑prone jobs. After the introduction of ChatGPT, there was a 21% decrease in the weekly number of posts in automation‑prone jobs compared to manual‑intensive jobs. Writing jobs were affected the most (30.37% decrease), followed by software, app, and web development (20.62%) and engineering (10.42%).

Internet: www.hbr.org (adapted).

The word “willingness” (second paragraph) can be replaced correctly by goodwill without any changes in meaning.

In the 1980s, plant genetic resources were considered under international law to be a common heritage of mankind, and were therefore classified as goods that cannot be owned. However, this status was strongly rejected by many emerging countries because it gave pharmaceutical and seed companies (mostly from rich countries) free access to their genetic resources without being required in any way to redistribute a share of their profits.

These countries scored a victory with the signing of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992 and the TRIPS agreement in 1995. Genetic resources now come under the control of sovereign countries, and some property rights can be recognized to the indigenous communities on the resources that they have been conserving from generation to generation. States are now required to organize these “collective intellectual property rights” in such a way that any local resource conserved in this manner will generate dividends for these populations when used by multinational firms.

The now well-known concept of Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit-Sharing (ABS) emerged in the second half of the 1990s. Their aim was to organize a biological diversity marketplace capable of enhancing the value of the genetic resources of countries of the South, which cannot refuse access to these resources. In addition, these countries can now claim a share of the profits that may result from their use.

In short, the change in the status of genetic resources from common heritage of mankind to a good that can be owned under national sovereignty took place in the early 1990s at the request of countries of the South and to their benefit, and the ABS mechanism is a fine example of intellectual property rights set up in the interest of the people of these countries.

In a general sense, this analysis is fairly accurate and could constitute an argument to be used against those who are of the opinion that the spread of intellectual property rights is an obstacle to the development of the South. However, the issue today is whether the South gained anything by playing this card. In answering this question, it is important to more clearly emphasize the deep connection—often overlooked—between the conservation of genetic resources and their practical use.

Internet: <https://shs.cairn.info/journal> (adapted).

Based on the preceding text, judge the following items.

According to the text, the ABS system was created to prevent multinational companies from using the genetic resources of countries of the South.

Art and Banking: from the House of Medici to Deutsche Bank

An example in coexistence – that is how we might define the intersection between the banking sector and the art world since the Middle Ages. Esses dois campos distintos gradualmente desenvolveram diversos pontos de contato, muitos dos quais persistem há séculos.In 2020, faced with the spread of Covid-19, people’s interest in illiquid art investments has diminished, but, given the long history of interactions between bankers and people of art, we may conclude that the historical trend is bound to spring back.

The first examples of cross-pollination between banking and art can be traced back to the 13th century, when wealthy financiers would acquire or commission masterpieces as a means of penitence for their sins and as a marker of social status.By the 16th century, as religious influences receded, bankers were motivated by the luxury of becoming patrons of the arts, mythologizing their individual power through art and architecture. The most well-known example of this trend was the Medici family, which sponsored the artistic development and posterity of Renaissance virtuosos such as Donatello, Michelangelo, Sandro Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci.In the 17th century, art became a consumer commodity, and would often be used as currency; artists were also known to use their work as collateral for loans. In the 18th and 19th centuries, banks would provide immeasurable support to the founders of the earliest art academies and national museums.

The turning point in this journey for art and banking came in the 1940s, when the art world’s centre of gravity suddenly shifted straight across the Atlantic, from Paris to Manhattan.In light of this tectonic shift, Chase Manhattan Bank president David Rockefeller launched the bank’s art collection programme, which would define the future vision of nearly every finance institution globally. It became one of the first few commercial art collections, as we know them today.

Currently, one of the largest commercial collections of artworks is owned by Deutsche Bank. From humble beginnings with the acquisition of the first few paintings, sculptures, photographs and graphics in 1979, it now reaches an estimated value of 500 million U.S. dollars – perhaps a diminutive figure in the grand scheme of things, but Deutsche Bank prefers to feature young, promising artists.The most valuable pieces in the Deutsche Bank collection had been acquired well before their respective authors became household names. Thus, the bank purchased Abstraktes Bild (Faust), Gerhard Richter’s 1981 triptych, for 12 million dollars; in February 2020, it was sold for triple the amount to an anonymous buyer.

Over time, we may observe how the relationship between artists and bankers has grown increasingly transactional since the Medici era. Today, art is still a hallmark of socioeconomic status, even though most bankers also treat art both as a financial investment and interior decoration that shapes the organisational climate and inspires personnel.Art collecting is often included under the umbrella of a marketing strategy, as a peculiar language of broadcasting organisational values. Where the common journey of banking and art may lead in later decades or centuries is difficult to predict, but one thing remains clear: art will remain a point of interest for bankers.

Available at: https://signetbank.com/en/news/art-and-banking--from-the-house-of-medici-to-deutsche-bank/. Retrieved on: March, 8th, 2025. Adapted.

From the fragment in the first paragraph of the text “In 2020, faced with the spread of Covid-19, people’s interest in illiquid art investments has diminished”, one can conclude that, in 2020, Covid-19 pandemic was

Text I

Understanding bias in facial recognition technologies

Over the past couple of years, the growing debate around automated facial recognition has reached a boiling point. As developers have continued to swiftly expand the scope of these kinds of technologies into an almost unbounded range of applications, an increasingly strident chorus of critical voices has sounded concerns about the injurious effects of the proliferation of such systems on impacted individuals and communities. Critics argue that the irresponsible design and use of facial detection and recognition technologies (FDRTs) threaten to violate civil liberties, infringe on basic human rights and further entrench structural racism and systemic marginalisation. In addition, they argue that the gradual creep of face surveillance infrastructures into every domain of lived experience may eventually eradicate the modern democratic forms of life that have long provided cherished means to individual flourishing, social solidarity and human self-creation.

Defenders, by contrast, emphasise the gains in public safety, security and efficiency that digitally streamlined capacities for facial identification, identity verification and trait characterisation may bring. These proponents point to potential real-world benefits like the added security of facial recognition enhanced border control, the increased efficacy of missing children or criminal suspect searches that are driven by the application of brute force facial analysis to largescale databases and the many added conveniences of facial verification in the business of everyday life.

Whatever side of the debate on which one lands, it would appear that FDRTs are here to stay.

Adapted from: understanding_bias_in_facial_recognition_technology.pdf

Based on Text I, analyze the assertions below:

I. Critics are concerned about the pervasiveness of facial recognition technology.

II. Facial recognition systems may reduce the efficiency and security of border control.

III. Some argue that the new technology could undermine the stability of modern democracy.

Choose the correct answer:

Text I

Understanding bias in facial recognition technologies

Over the past couple of years, the growing debate around automated facial recognition has reached a boiling point. As developers have continued to swiftly expand the scope of these kinds of technologies into an almost unbounded range of applications, an increasingly strident chorus of critical voices has sounded concerns about the injurious effects of the proliferation of such systems on impacted individuals and communities. Critics argue that the irresponsible design and use of facial detection and recognition technologies (FDRTs) threaten to violate civil liberties, infringe on basic human rights and further entrench structural racism and systemic marginalisation. In addition, they argue that the gradual creep of face surveillance infrastructures into every domain of lived experience may eventually eradicate the modern democratic forms of life that have long provided cherished means to individual flourishing, social solidarity and human self-creation.

Defenders, by contrast, emphasise the gains in public safety, security and efficiency that digitally streamlined capacities for facial identification, identity verification and trait characterisation may bring. These proponents point to potential real-world benefits like the added security of facial recognition enhanced border control, the increased efficacy of missing children or criminal suspect searches that are driven by the application of brute force facial analysis to largescale databases and the many added conveniences of facial verification in the business of everyday life.

Whatever side of the debate on which one lands, it would appear that FDRTs are here to stay.

Adapted from: understanding_bias_in_facial_recognition_technology.pdf

The word “like” in “like the added security of facial recognition” (2nd paragraph) introduces a(n)

In the early 2000s, when Amazon introduced its Kiva robots to automate warehouse operations, employees feared for their jobs as machines began taking over tasks previously performed by humans. Today, advances in gen AI and natural language processing, such as ChatGPT, are transforming many industries and raising similar concerns. However, unlike past automation technologies, gen AI has the unique potential to impact all job sectors, particularly given its fundamental ability to improve its capabilities over time – which promises to affect the workforce in ways that go beyond simple job replacement.

In new research, forthcoming in Management Science, we explore the impact gen AI has already had on the labor market by examining trends in demand for online freelancers. Our findings show significant short‑term job replacement after these tools were introduced, and that jobs prone to automation, like writing and coding, were the most affected by ChatGPT.Our research also examines how competition, job requirements, and employer willingness‑to‑pay have changed to better understand how the online job market is evolving with the rise of gen AI. Although still in its early stages, gen AI’s impact on online labor markets is already becoming discernible, suggesting potential shifts in long‑term labor market dynamics that could bring both challenges and opportunities.

To conduct our study, we analyzed 1.388.711 job posts from a leading global online freelancing platform from July 2021 to July 2023. Online freelancing platforms provide a good setting for examining emerging trends due to the digital, task‑oriented, and flexible nature of work on these platforms. We focus our analysis on the introduction of two types of gen AI tools: ChatGPT and image‑generating AI. Specifically, we wanted to understand whether the introduction and diffusion of these tools decreased demand for jobs on this platform and, if so, which types of jobs and skills are affected most and by how much.

Using a machine learning algorithm, we first grouped job posts into different categories based on their detailed job descriptions. These categories were then classified into three types: manual‑intensive jobs (e.g., data and office management, video services, and audio services), automation‑prone jobs (e.g., writing; software, app, and web development; engineering), and image‑generating jobs (e.g., graphic design and 3D modeling). We then examined the impact that the introduction of Gen AI tools had on demand across these different types of jobs.

We find that the introduction of ChatGPT and image‑generating tools led to nearly immediate decreases in posts for online gig workers across job types, but particularly for automation‑prone jobs. After the introduction of ChatGPT, there was a 21% decrease in the weekly number of posts in automation‑prone jobs compared to manual‑intensive jobs. Writing jobs were affected the most (30.37% decrease), followed by software, app, and web development (20.62%) and engineering (10.42%).

Internet: www.hbr.org (adapted).

The researchers discovered that Artificial Intelligence has increased automation-prone jobs, especially compared to manual-intensive jobs.

In the early 2000s, when Amazon introduced its Kiva robots to automate warehouse operations, employees feared for their jobs as machines began taking over tasks previously performed by humans. Today, advances in gen AI and natural language processing, such as ChatGPT, are transforming many industries and raising similar concerns. However, unlike past automation technologies, gen AI has the unique potential to impact all job sectors, particularly given its fundamental ability to improve its capabilities over time – which promises to affect the workforce in ways that go beyond simple job replacement.

In new research, forthcoming in Management Science, we explore the impact gen AI has already had on the labor market by examining trends in demand for online freelancers. Our findings show significant short‑term job replacement after these tools were introduced, and that jobs prone to automation, like writing and coding, were the most affected by ChatGPT.Our research also examines how competition, job requirements, and employer willingness‑to‑pay have changed to better understand how the online job market is evolving with the rise of gen AI. Although still in its early stages, gen AI’s impact on online labor markets is already becoming discernible, suggesting potential shifts in long‑term labor market dynamics that could bring both challenges and opportunities.

To conduct our study, we analyzed 1.388.711 job posts from a leading global online freelancing platform from July 2021 to July 2023. Online freelancing platforms provide a good setting for examining emerging trends due to the digital, task‑oriented, and flexible nature of work on these platforms. We focus our analysis on the introduction of two types of gen AI tools: ChatGPT and image‑generating AI. Specifically, we wanted to understand whether the introduction and diffusion of these tools decreased demand for jobs on this platform and, if so, which types of jobs and skills are affected most and by how much.

Using a machine learning algorithm, we first grouped job posts into different categories based on their detailed job descriptions. These categories were then classified into three types: manual‑intensive jobs (e.g., data and office management, video services, and audio services), automation‑prone jobs (e.g., writing; software, app, and web development; engineering), and image‑generating jobs (e.g., graphic design and 3D modeling). We then examined the impact that the introduction of Gen AI tools had on demand across these different types of jobs.

We find that the introduction of ChatGPT and image‑generating tools led to nearly immediate decreases in posts for online gig workers across job types, but particularly for automation‑prone jobs. After the introduction of ChatGPT, there was a 21% decrease in the weekly number of posts in automation‑prone jobs compared to manual‑intensive jobs. Writing jobs were affected the most (30.37% decrease), followed by software, app, and web development (20.62%) and engineering (10.42%).

Internet: www.hbr.org (adapted).

The researchers used different job categories in their study. All of them use technology, like data and office management.

In the 1980s, plant genetic resources were considered under international law to be a common heritage of mankind, and were therefore classified as goods that cannot be owned. However, this status was strongly rejected by many emerging countries because it gave pharmaceutical and seed companies (mostly from rich countries) free access to their genetic resources without being required in any way to redistribute a share of their profits.

These countries scored a victory with the signing of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) in 1992 and the TRIPS agreement in 1995. Genetic resources now come under the control of sovereign countries, and some property rights can be recognized to the indigenous communities on the resources that they have been conserving from generation to generation. States are now required to organize these “collective intellectual property rights” in such a way that any local resource conserved in this manner will generate dividends for these populations when used by multinational firms.

The now well-known concept of Access to Genetic Resources and Benefit-Sharing (ABS) emerged in the second half of the 1990s. Their aim was to organize a biological diversity marketplace capable of enhancing the value of the genetic resources of countries of the South, which cannot refuse access to these resources. In addition, these countries can now claim a share of the profits that may result from their use.

In short, the change in the status of genetic resources from common heritage of mankind to a good that can be owned under national sovereignty took place in the early 1990s at the request of countries of the South and to their benefit, and the ABS mechanism is a fine example of intellectual property rights set up in the interest of the people of these countries.

In a general sense, this analysis is fairly accurate and could constitute an argument to be used against those who are of the opinion that the spread of intellectual property rights is an obstacle to the development of the South. However, the issue today is whether the South gained anything by playing this card. In answering this question, it is important to more clearly emphasize the deep connection—often overlooked—between the conservation of genetic resources and their practical use.

Internet: <https://shs.cairn.info/journal> (adapted).

Based on the preceding text, judge the following items.

The word “However”, in the second sentence of the last paragraph, can be correctly replaced with Nevertheless, without changing the original meaning of the fragment.

Art and Banking: from the House of Medici to Deutsche Bank

An example in coexistence – that is how we might define the intersection between the banking sector and the art world since the Middle Ages. Esses dois campos distintos gradualmente desenvolveram diversos pontos de contato, muitos dos quais persistem há séculos.In 2020, faced with the spread of Covid-19, people’s interest in illiquid art investments has diminished, but, given the long history of interactions between bankers and people of art, we may conclude that the historical trend is bound to spring back.

The first examples of cross-pollination between banking and art can be traced back to the 13th century, when wealthy financiers would acquire or commission masterpieces as a means of penitence for their sins and as a marker of social status.By the 16th century, as religious influences receded, bankers were motivated by the luxury of becoming patrons of the arts, mythologizing their individual power through art and architecture. The most well-known example of this trend was the Medici family, which sponsored the artistic development and posterity of Renaissance virtuosos such as Donatello, Michelangelo, Sandro Botticelli and Leonardo da Vinci.In the 17th century, art became a consumer commodity, and would often be used as currency; artists were also known to use their work as collateral for loans. In the 18th and 19th centuries, banks would provide immeasurable support to the founders of the earliest art academies and national museums.

The turning point in this journey for art and banking came in the 1940s, when the art world’s centre of gravity suddenly shifted straight across the Atlantic, from Paris to Manhattan.In light of this tectonic shift, Chase Manhattan Bank president David Rockefeller launched the bank’s art collection programme, which would define the future vision of nearly every finance institution globally. It became one of the first few commercial art collections, as we know them today.

Currently, one of the largest commercial collections of artworks is owned by Deutsche Bank. From humble beginnings with the acquisition of the first few paintings, sculptures, photographs and graphics in 1979, it now reaches an estimated value of 500 million U.S. dollars – perhaps a diminutive figure in the grand scheme of things, but Deutsche Bank prefers to feature young, promising artists.The most valuable pieces in the Deutsche Bank collection had been acquired well before their respective authors became household names. Thus, the bank purchased Abstraktes Bild (Faust), Gerhard Richter’s 1981 triptych, for 12 million dollars; in February 2020, it was sold for triple the amount to an anonymous buyer.

Over time, we may observe how the relationship between artists and bankers has grown increasingly transactional since the Medici era. Today, art is still a hallmark of socioeconomic status, even though most bankers also treat art both as a financial investment and interior decoration that shapes the organisational climate and inspires personnel.Art collecting is often included under the umbrella of a marketing strategy, as a peculiar language of broadcasting organisational values. Where the common journey of banking and art may lead in later decades or centuries is difficult to predict, but one thing remains clear: art will remain a point of interest for bankers.

Available at: https://signetbank.com/en/news/art-and-banking--from-the-house-of-medici-to-deutsche-bank/. Retrieved on: March, 8th, 2025. Adapted.

The main purpose of the text is to describe the association between banking and