Texto – A eficácia das palavras certas

Havia um cego sentado numa calçada em Paris. A seus pés, um

boné e um cartaz em madeira escrito com giz branco gritava:

“Por favor, ajude-me. Sou cego". Um publicitário da área de

criação, que passava em frente a ele, parou e viu umas poucas

moedas no boné. Sem pedir licença, pegou o cartaz e com o giz

escreveu outro conceito. Colocou o pedaço de madeira aos pés

do cego e foi embora.

Ao cair da tarde, o publicitário voltou a passar em frente ao cego

que pedia esmola. Seu boné, agora, estava cheio de notas e

moedas. O cego reconheceu as pegadas do publicitário e

perguntou se havia sido ele quem reescrevera o cartaz,

sobretudo querendo saber o que ele havia escrito.

O publicitário respondeu: “Nada que não esteja de acordo com o

conceito original, mas com outras palavras". E, sorrindo,

continuou o seu caminho. O cego nunca soube o que estava

escrito, mas seu novo cartaz dizia: “Hoje é primavera em Paris e

eu não posso vê-la". (Produção de Texto, Maria Luíza M. Abaurre

e Maria Bernadete M. Abaurre)

O título dado ao texto:

Texto – A eficácia das palavras certas

Havia um cego sentado numa calçada em Paris. A seus pés, um

boné e um cartaz em madeira escrito com giz branco gritava:

"Por favor, ajude-me. Sou cego". Um publicitário da área de

criação, que passava em frente a ele, parou e viu umas poucas

moedas no boné. Sem pedir licença, pegou o cartaz e com o giz

escreveu outro conceito. Colocou o pedaço de madeira aos pés

do cego e foi embora.

Ao cair da tarde, o publicitário voltou a passar em frente ao cego

que pedia esmola. Seu boné, agora, estava cheio de notas e

moedas. O cego reconheceu as pegadas do publicitário e

perguntou se havia sido ele quem reescrevera o cartaz,

sobretudo querendo saber o que ele havia escrito.

O publicitário respondeu: "Nada que não esteja de acordo com o

conceito original, mas com outras palavras". E, sorrindo,

continuou o seu caminho. O cego nunca soube o que estava

escrito, mas seu novo cartaz dizia: "Hoje é primavera em Paris e

eu não posso vê-la". (Produção de Texto, Maria Luíza M. Abaurre

e Maria Bernadete M. Abaurre)

“Sem pedir licença, pegou o cartaz e com o giz escreveu outro conceito”; a oração “Sem pedir licença” pode ser adequadamente substituída pela seguinte oração desenvolvida:

READ TEXT I AND ANSWER QUESTIONS 11 TO 15

TEXT I

Will computers ever truly understand what we're saying?

Date: January 11, 2016

Source University of California - Berkeley

Summary:

If you think computers are quickly approaching true human

communication, think again. Computers like Siri often get

confused because they judge meaning by looking at a word's

statistical regularity. This is unlike humans, for whom context is

more important than the word or signal, according to a

researcher who invented a communication game allowing only

nonverbal cues, and used it to pinpoint regions of the brain where

mutual understanding takes place.

From Apple's Siri to Honda's robot Asimo, machines seem to be

getting better and better at communicating with humans. But

some neuroscientists caution that today's computers will never

truly understand what we're saying because they do not take into

account the context of a conversation the way people do.

Specifically, say University of California, Berkeley, postdoctoral

fellow Arjen Stolk and his Dutch colleagues, machines don't

develop a shared understanding of the people, place and

situation - often including a long social history - that is key to

human communication. Without such common ground, a

computer cannot help but be confused.

"People tend to think of communication as an exchange of

linguistic signs or gestures, forgetting that much of

communication is about the social context, about who you are

communicating with," Stolk said.

The word "bank," for example, would be interpreted one way if

you're holding a credit card but a different way if you're holding a

fishing pole. Without context, making a "V" with two fingers

could mean victory, the number two, or "these are the two

fingers I broke."

"All these subtleties are quite crucial to understanding one

another," Stolk said, perhaps more so than the words and signals

that computers and many neuroscientists focus on as the key to

communication. "In fact, we can understand one another without

language, without words and signs that already have a shared

meaning."

(Adapted from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/01/1

60111135231.htm)

Based on the summary provided for Text I, mark the statements below as TRUE (T ) or FALSE (F ). ( ) Contextual clues are still not accounted for by computers. ( ) Computers are unreliable because they focus on language patterns. ( ) A game has been invented based on the words people use. The statements are, respectively:

READ TEXT II AND ANSWER QUESTIONS 16 TO 20:

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large

body of data that weren't possible when working with smaller

amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to

massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet

search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voicerecognition

and translation, for example) that work

well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the

application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from

retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March,

prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at

Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data

poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified

flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the

number of cases for four years running, compared with reported

data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a

wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big

data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit.

First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored.

That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data

have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the

world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains

necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk

of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust

but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although

there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish

spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets

of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But

these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit

whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data

"hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends

analysis with CDC's data improved the overall forecast—showing

that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published

in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible

to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia

articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the

classic hype cycle, in which a technology's early proponents make

overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those

promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the

world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It

happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures

and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data's turn to

face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201

4/04/economist-explains-10)

When Text II mentions “grumblers” in “to face the grumblers”, it refers to:

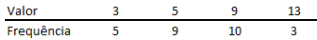

Após a extração de uma amostra, as observações obtidas são

tabuladas, gerando a seguinte distribuição de frequências:

Considerando que E(X ) = Média de X, Mo(X ) = Moda de X e Me(X )

= Mediana de X, é correto afirmar que:

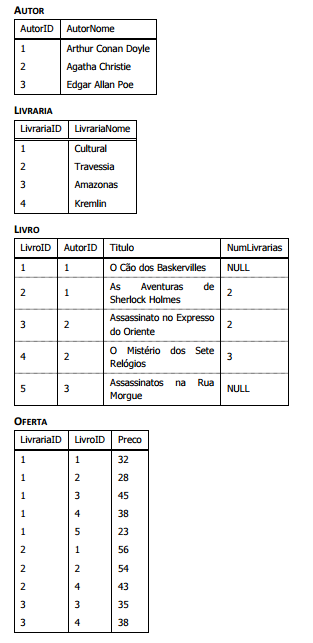

Atenção: Algumas das questões seguintes fazem referência a um banco de dados relacional intitulado BOOKS, cujas tabelas e respectivas instâncias são exibidas a seguir. Essas questões referem-se às instâncias mostradas.

A tabela Livro representa livros. Cada livro tem um autor, representado na tabela Autor. A tabela Oferta representa os livros que são ofertados pelas livrarias, estas representadas pela tabela Livraria. NULL significa um campo não preenchido. AutorID, LivrariaID e LivroID, respectivamente, constituem as chaves primárias das tabelas Autor, Livraria e Livro. LivrariaID e LivroID constituem a chave primária da tabela Oferta.

Com relação ao banco de dados BOOKS, analise os comandos SQL

exibidos a seguir:

I.select *

from oferta o, livro l, autor a, livraria ll

where o.livroid=l.livroid and

o.livrariaid=ll.livrariaid and l.autorid=a.autorid

II.select *

from oferta o inner join livro l on

o.livroid=l.livroid

inner join autor a on l.autorid=a.autorid

inner join livraria ll on

o.livrariaid=ll.livrariaid

III.select *

from oferta o left join livro l on

o.livroid=l.livroid

left join autor a on l.autorid=a.autorid

left join livraria ll on

o.livrariaid=ll.livrariaid

É correto afirmar que:

Algumas das mais importantes implementações de bancos de

dados relacionais dispõem do comando TRUNCATE para remover

registros de uma tabela.

Considere as seguintes opções para remover registros de uma

tabela T:

I.Usando o comando DELETE;

II.Usando o comando TRUNCATE;

III.Removendo a tabela T e executando um comando CREATE

TABLE para recriá-la em seguida.

Sobre essas opções, é correto afirmar que:

Analise o código Java a seguir: import java.io.*; import java.util.regex.Pattern; class XX { public static void main(String args[]) { Pattern p = Pattern.compile(" "); String tmp = "Apenas um texto a mais"; String[] tokens = p.split(tmp); for (int i = 0; i < tokens.length; i++) { System.out.println(tokens[i]); } } } Com referência ao texto atribuído à variável tmp, o resultado exibido contém:

Analise o código C# exibido a seguir:

using System;

namespace ENIGMA

{

class Program {

static void Main(string[] args) {

P d = new P();

d.PP();

E s = new E();

s.A();

s.PP();

Console.ReadKey();

}

class P {

public void PP()

{

Console.WriteLine("PP");

}

}

class E : P {

public void A()

{

Console.WriteLine("A");

}

}

}

}

O resultado produzido no console é:

Com relação ao estabelecimento de conexões do protocolo TCP, analise as afirmativas a seguir: I.Na solicitação de conexão do tipo abertura ativa, um segmento SYN não transporta dados e consome um número de sequência. II.O procedimento de estabelecimento de conexão é suscetível a problemas de segurança e os ataques são do tipo SYN Flooding attack. III.O TCP transmite dados em modo half-duplex e o estabelecimento de conexão é denominado three-way handshaking. Está correto somente o que se afirma em:

A empresa SONOVATOS desenvolve sistemas há pouco tempo no mercado e, como padrão, sempre utilizou o modelo Cascata de ciclo de vida. Alguns clientes ficaram insatisfeitos com os produtos desenvolvidos pela empresa por não estarem de acordo com suas necessidades. Atualmente a SONOVATOS está desenvolvendo sistemas muito maiores, com duração de vários anos, e com requisitos ainda instáveis. O próprio processo de desenvolvimento da empresa também está em reformulação. Assim, a adoção de um novo modelo de ciclo de vida está sendo avaliada pelos gerentes da empresa. A intenção da SONOVATOS é, principalmente, gerenciar riscos e poder reavaliar constantemente o processo de desenvolvimento ao longo do projeto, o que permitiria correções nesse processo ou até mudança do tipo de processo. O modelo mais adequado para os sistemas atuais de longa duração da SONOVATOS é:

Texto – A eficácia das palavras certas

Havia um cego sentado numa calçada em Paris. A seus pés, um

boné e um cartaz em madeira escrito com giz branco gritava:

"Por favor, ajude-me. Sou cego". Um publicitário da área de

criação, que passava em frente a ele, parou e viu umas poucas

moedas no boné. Sem pedir licença, pegou o cartaz e com o giz

escreveu outro conceito. Colocou o pedaço de madeira aos pés

do cego e foi embora.

Ao cair da tarde, o publicitário voltou a passar em frente ao cego

que pedia esmola. Seu boné, agora, estava cheio de notas e

moedas. O cego reconheceu as pegadas do publicitário e

perguntou se havia sido ele quem reescrevera o cartaz,

sobretudo querendo saber o que ele havia escrito.

O publicitário respondeu: "Nada que não esteja de acordo com o

conceito original, mas com outras palavras". E, sorrindo,

continuou o seu caminho. O cego nunca soube o que estava

escrito, mas seu novo cartaz dizia: "Hoje é primavera em Paris e

eu não posso vê-la". (Produção de Texto, Maria Luíza M. Abaurre

e Maria Bernadete M. Abaurre)

“Por favor, ajude-me. Sou cego"; reescrevendo as duas frases em

uma só, de forma correta e respeitando-se o sentido original, a

estrutura adequada é:

READ TEXT I AND ANSWER QUESTIONS 11 TO 15

TEXT I

Will computers ever truly understand what we're saying?

Date: January 11, 2016

Source University of California - Berkeley

Summary:

If you think computers are quickly approaching true human

communication, think again. Computers like Siri often get

confused because they judge meaning by looking at a word's

statistical regularity. This is unlike humans, for whom context is

more important than the word or signal, according to a

researcher who invented a communication game allowing only

nonverbal cues, and used it to pinpoint regions of the brain where

mutual understanding takes place.

From Apple's Siri to Honda's robot Asimo, machines seem to be

getting better and better at communicating with humans. But

some neuroscientists caution that today's computers will never

truly understand what we're saying because they do not take into

account the context of a conversation the way people do.

Specifically, say University of California, Berkeley, postdoctoral

fellow Arjen Stolk and his Dutch colleagues, machines don't

develop a shared understanding of the people, place and

situation - often including a long social history - that is key to

human communication. Without such common ground, a

computer cannot help but be confused.

“People tend to think of communication as an exchange of

linguistic signs or gestures, forgetting that much of

communication is about the social context, about who you are

communicating with," Stolk said.

The word “bank," for example, would be interpreted one way if

you're holding a credit card but a different way if you're holding a

fishing pole. Without context, making a “V" with two fingers

could mean victory, the number two, or “these are the two

fingers I broke."

“All these subtleties are quite crucial to understanding one

another," Stolk said, perhaps more so than the words and signals

that computers and many neuroscientists focus on as the key to

communication. “In fact, we can understand one another without

language, without words and signs that already have a shared

meaning."

(Adapted from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/01/1

60111135231.htm)

The title of Text I reveals that the author of this text is:

READ TEXT II AND ANSWER QUESTIONS 16 TO 20:

TEXT II

The backlash against big data

[…]

Big data refers to the idea that society can do things with a large

body of data that weren't possible when working with smaller

amounts. The term was originally applied a decade ago to

massive datasets from astrophysics, genomics and internet

search engines, and to machine-learning systems (for voicerecognition

and translation, for example) that work

well only when given lots of data to chew on. Now it refers to the

application of data-analysis and statistics in new areas, from

retailing to human resources. The backlash began in mid-March,

prompted by an article in Science by David Lazer and others at

Harvard and Northeastern University. It showed that a big-data

poster-child—Google Flu Trends, a 2009 project which identified

flu outbreaks from search queries alone—had overestimated the

number of cases for four years running, compared with reported

data from the Centres for Disease Control (CDC). This led to a

wider attack on the idea of big data.

The criticisms fall into three areas that are not intrinsic to big

data per se, but endemic to data analysis, and have some merit.

First, there are biases inherent to data that must not be ignored.

That is undeniably the case. Second, some proponents of big data

have claimed that theory (ie, generalisable models about how the

world works) is obsolete. In fact, subject-area knowledge remains

necessary even when dealing with large data sets. Third, the risk

of spurious correlations—associations that are statistically robust

but happen only by chance—increases with more data. Although

there are new statistical techniques to identify and banish

spurious correlations, such as running many tests against subsets

of the data, this will always be a problem.

There is some merit to the naysayers' case, in other words. But

these criticisms do not mean that big-data analysis has no merit

whatsoever. Even the Harvard researchers who decried big data

"hubris" admitted in Science that melding Google Flu Trends

analysis with CDC's data improved the overall forecast—showing

that big data can in fact be a useful tool. And research published

in PLOS Computational Biology on April 17th shows it is possible

to estimate the prevalence of the flu based on visits to Wikipedia

articles related to the illness. Behind the big data backlash is the

classic hype cycle, in which a technology's early proponents make

overly grandiose claims, people sling arrows when those

promises fall flat, but the technology eventually transforms the

world, though not necessarily in ways the pundits expected. It

happened with the web, and television, radio, motion pictures

and the telegraph before it. Now it is simply big data's turn to

face the grumblers.

(From http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist explains/201

4/04/economist-explains-10)

The base form, past tense and past participle of the verb “fall” in “The criticisms fall into three areas” are, respectively:

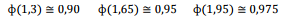

Sabe-se que as notas de uma prova têm distribuição Normal

com média μ=6,5 e variância α²=4. Adicionalmente, são

conhecidos alguns valores tabulados da normal-padrão.

Onde, é a função distribuição acumulada da Normal Padrão.

é a função distribuição acumulada da Normal Padrão.

Considerando-se que apenas os 10% que atinjam as maiores notas

serão aprovados, a nota mínima para aprovação é: